Something that has always astounded me is the vast amount of information tucked away in some corner of our minds, out of reach. We’ve all spent our entire lives engaged in some activity or another and provide our brains a constant stream of input. A small percentage of this input sticks, while most seemingly disappears. However, I don’t believe this data is completely gone — it’s merely hidden.

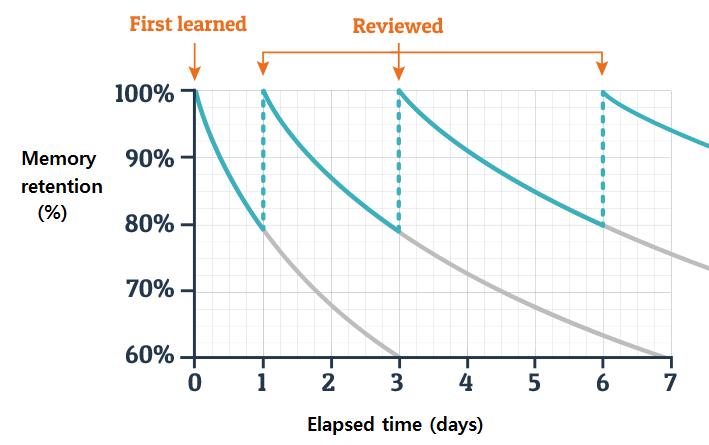

Biologically, our brains are complex and messy. Input from the outside world gets encoded as electrical signals between neurons that are themselves connected to other neurons. This associative structure is the basis for “creativity” and is why we can bridge seemingly distinct ideas. Over time, these connections weaken if not actively strengthened — conversely they become increasingly resilient the more repetitions we give to a particular network of thoughts. This property can be represented by the “forgetting curve” and is the basis for spaced repetition, habits, and addictions.

The Forgetting Curve

We’ve all experienced some fashion of the cliché “it’s just like riding a bike”. If you strengthen the neural connectivity of an activity or idea enough times at the right intervals, the forgetting curve becomes nearly flat and you’ll find yourself retaining a substantial amount of the information, even decades later. Perhaps with enough time and entropy, you’ll eventually forget but with the realistic upper bound of a human lifespan set to around 100, this property can be leveraged as a useful tool through spaced repetition (which I plan to write more about in the future).

More immediately, I experienced this phenomenon with regards to language learning. Back in 2018, I lived in Spain for 5 months and had immersed myself in the Spanish language at the time (grammar classes, language exchanges, daily practice, and Gran Hotel).

I recently took a trip to Madrid with some friends — my first time there since 2018. It had been years since I’d spoken a full sentence or even thought about Spanish in a cognitively demanding way, and assumed that I was back to square one. This assumption pushed me to let my lads take the lead in translational situations, while I sat back and waited for the English.

A few days in, I found myself in a smaller group of lads, in which I was the expert in Spanish and thus became the de-facto translator. I was at the front desk of a gym, trying to get in while navigating the complex rules around Covid19 restrictions. My heart was racing, but I dove in and just started talking. My grammar was atrocious, but the kind lady at the desk could understand me, and slowed down her staccato Castilian accent to accommodate this goofy foreigner who was fiending for a sauna.

Afterwards, I felt an immense pressure lifted off my shoulder. I could actually communicate in Spanish without Google Translate. The high I got from this was so great that I spent the rest of the day making up excuses to talk to random people including an Uber driver, a museum docent, and a restaurant owner. My intense and immersive practice in 2018 had planted seeds, the fruits of which I was just starting to harvest, years down the line.

The individual pedals involved in “riding a bike” might seem meaningless in the moment, but they ultimately add up a more cohesive grasp in the future. The key here is learning to get over the initial hurdle and face the discomfort head on. You might stumble and fall a few times, but soon you’ll be soaring.