🩸 Monitoring my Blood Sugar as a Non-Diabetic

January 10, 2022 • 13 min read

I used a continuous glucose monitor for a month as a non-diabetic — here’s what I learned.

As I get older, I find myself continuing to optimize my health under the guidance of one core principle — that most of the negativity I experience externally is caused by internal biological factors (poor sleep, blood sugar crash, nutrient deficiency, etc.)

Earlier this year, I used a continuous glucose monitor for a month. Even though I don't have any early markers for metabolic issues, I wanted to see what I could learn.

One of my learnings was this notion of "metabolic health" which can be measured by blood sugar, triglycerides, cholesterol, blood pressure, and other data points. Metabolism is multi-faceted, but can be thought of as the process by which your body converts input (food & drink) into energy. The health of this process is crucial as it directly relates to your long-term risk for heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and more immediate concerns like your energy on any given Tuesday.

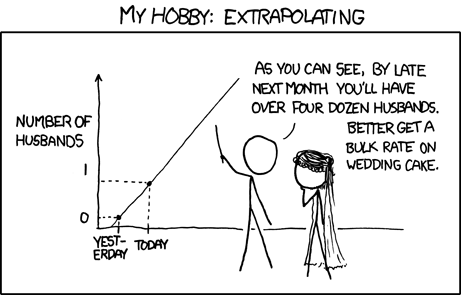

One of the best ways to get a read on your metabolism is by measuring your blood sugar. However, most of us have only one data point to reference — our annual physical. This data point (if we even manage to get it) is inherently flawed as it takes a single snapshot of blood sugar while fasted and extrapolates that to an entire year's worth of health. This data point can be useful to understand if we have acute glucose insensitivity or early indications of diabetes — but what about understanding how a pastry might affect your mood the rest of the day? I don’t need to explain why extrapolation from a single point of data is a bad idea:

On Glucose Monitoring

Glucose monitoring has evolved over the years from unreliable urine testing, to machines that draw lots of blood, to more recent finger prick systems. In 1999, the first continuous glucose monitor (CGM) was approved as a stylish wrist watch that could continuously monitor blood sugar levels, but it didn't find widespread adoption since it was quite invasive. As the century progressed, Dexcom, Abbot, and Medtronic continued to make improvements on the design and created an non-invasive device that could monitor blood sugar levels through a small layer of fluid (interstitial) beneath the skin.

[TODO: guy sweating near large machine for drawing blood]

🩸 Enter the Modern & Ubiquitous CGM 🩸

The modern-day CGM is an incredible tool to those suffering from metabolic issues. It gives them a first line of defense without painful hand pricks or nauseating blood draws, and also lets them track metabolic health over time. However, unless a doctor suggests that you need one for acute issues, you're trapped behind the expensive walled gardens of insurance companies.

This is one of my major gripes with modern health — there's too much of a focus on reactive health and not enough on preventive or proactive health. If you're like me and ask a doctor for a CGM with no indication of prior metabolic issues, they'll look at you like you're crazy and might even make you feel guilty for wanting one. The fact is that this technology is ubiquitous and easily accessible for those that need it, there just isn't a strong business model for preventative healthcare yet.

Recently, companies have been popping up that leverage telemedicine to connect you with a physician that can prescribe you a CGM. Typically, these services are not covered by insurance (yet) so you'll have to pay out of pocket for being on the bleeding edge. The company that I used is Levels Health, but there are many other options so I suggest doing some research. You can check Levels out here.

Levels Health

Why a CGM?

You might be wondering why it's worth spending out-of-pocket money to stick something on your arm just to track a health metric. It's difficult to justify all the time and financial investment into preventative health since the fruits of your labor are harder to see, so here are a few reasons why I decided to give it a shot.

Metabolic Awareness

When experimenting with a CGM, there's a strong feedback loop that you can leverage to gain a better intuitive understanding of your health:

- Consume some food or drink

- Take note of how you subjectively feel afterwards

- Map your measured blood sugar onto your subjective experience

This trains you to build "metabolic awareness" and is the same process that I've used to optimize my sleep with a tracker. Eventually, you learn what a healthy blood sugar response feels like and can ditch the tracker altogether.

It's one thing to talk about the "food coma" after an egregious meal, another thing to experience it after Thanksgiving dinner, and another thing entirely to feel the lethargy come on as you watch your glucose tick upwards in realtime. From my journal:

9/3/21 @ 8:47p — I've been pretty healthy all day and my numbers have been stable, but I decided to have a packet of Pocky. It ****ed me up. It's been an hour and my sugar is the highest it's been all day and I genuinely feel as though I'm crashing. How did I not make this connection in the past?

Our bodies are continually bombarded with stimuli and it's impossible to notice it all, so naturally our brains have excellent filtration systems. Even though you might feel like crap, it's hard to attribute that feeling to a particular choice of food unless you're actively tracking it. That's what a CGM can do — it can provide a level of intentionality into your daily diet and give you an awareness of what the end-to-end experience of eating something is actually like.

Personal Biology

Another issue with modern health at scale is the prevalence of one-size-fits-all solutions. There isn't enough incentive within our current system for doctors to give you personalized solutions to your health problems (unless you pay hefty out-of-pocket fees), so this is one area to take into your own hands.

We all react slightly differently to various kinds of food due to our genetic makeup. These variations aren't taken into consideration unless you actually test them. For example, I tend to react much better to rice compared to pasta. I attribute this primarily to my Indian heritage, and is a data point that I can use to improve my health long-term.

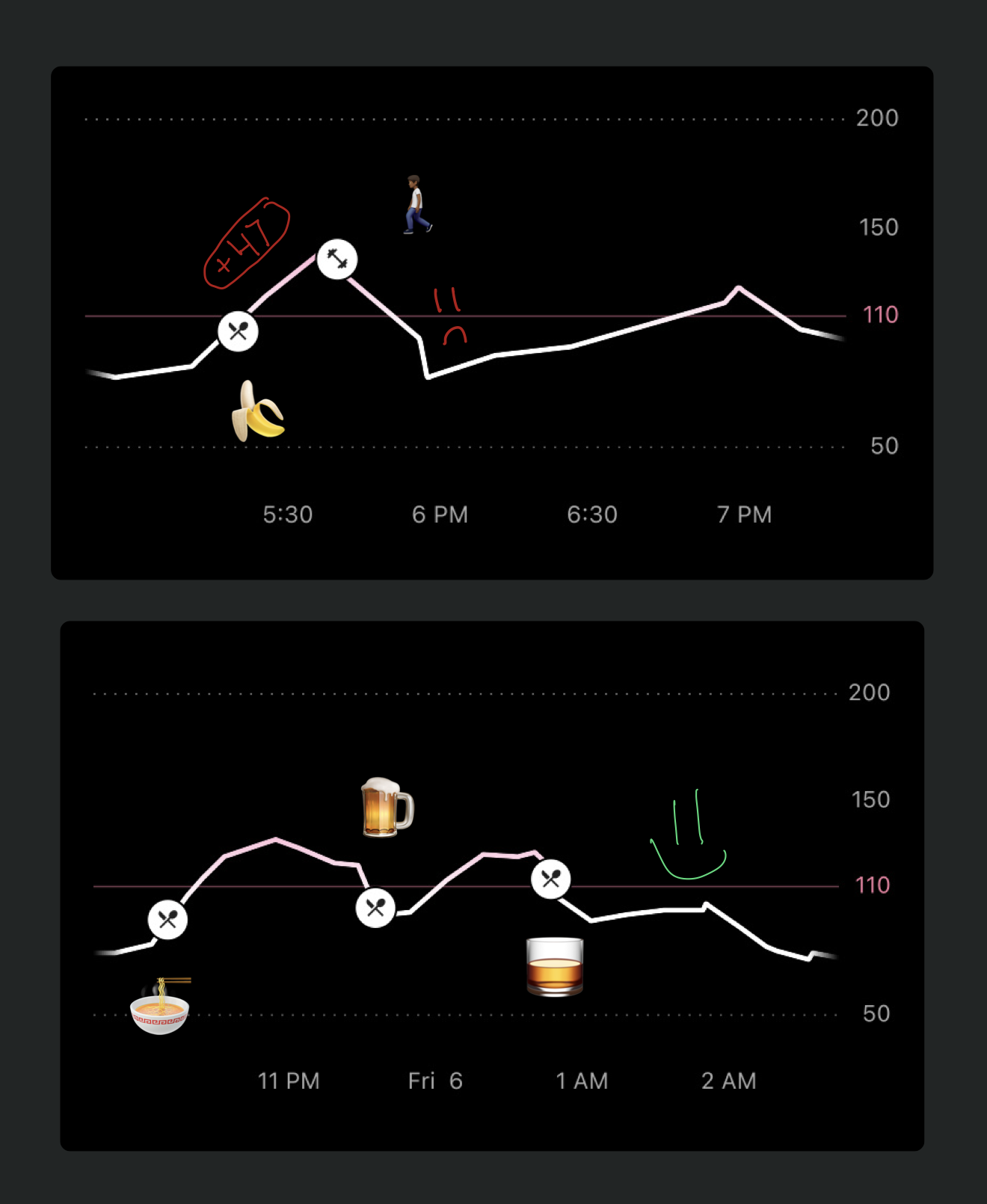

my little sister's perception of me

Another interesting finding was that a couple of bananas spiked my blood sugar more than a whole bowl of thick ramen, whiskey, and a few Guinness beers. Maybe there's a reason Peter Attia has cut bananas out of his diet in recent years.1

Experimenting with a CGM

Unless it's deemed "medically necessary", using a CGM isn't cheap. Just a month of the service (as of writing in 2021) will be around $300 - $400. Thus, it behooves you to use the CGM most effectively — in a way that allows you to maximize the amount of information you can glean from it.

The biggest thing I'd suggest here is to keep a journal and gather qualitative data each time you eat something — it's tedious but will be helpful as you assemble an action plan for yourself. Here's what I'd suggest:

- Take note of how you feel from eating 🍲

- Guess how much 🍲 spiked your blood sugar, and measure that to the recorded spike

- Reflect on why 🍲 might have done what it did to your blood sugar

This is a fine strategy throughout the day, but is subject to confounding variables (aka life) such as the effects of stress, exercise, time of day, etc.

If you only do this practice once, I'd suggest doing it first thing in the morning so that you can measure the effect of eating 🍲 in a fasted state. This provides the most accurate and honest measurement of your metabolic reaction to something.

Common Questions

Going into this, I had a lot of questions and knew very little about metabolic health, blood sugar, and everything involved in tracking this stuff. Here is a non-exhaustive list of everything that I've learned from my research and clinical n-of-1 experience.

Q: What's the difference between glucose and blood sugar?

A: From a metabolic perspective, these terms are the same. Continuous Blood Sugar Monitor (CBSM) just doesn't have the same ring to it…

Q: How do you put on a glucose monitor?

A: It's actually quite easy. It doesn't hurt at all, but the positioning of the monitor itself is important — you want to make sure it's on a relatively fleshy part of your upper arm. With the magic of adhesive, the CGM stays on your skin and the small needle monitors your blood sugar for as long as it lasts.

Q: What are the downsides for someone who doesn't already have metabolic issues?

A: There is a trivially low risk of physical harm as modern CGMs are noninvasive and well-understood. The main downsides are (1) possible psychological issues for people that tend to get anxious about their consumption or obsess over metrics and (2) the fact that it is expensive and not covered by insurance.

Q: What is the glycemic index and how does it relate to this?

A: The glycemic index is a metric used to determine how much a specific food will spike blood sugar levels. A lower number means a more stable response. Here’s a great resource for figuring out the glycemic index for almost any food you might come across.

Q: How does stress influence blood sugar?

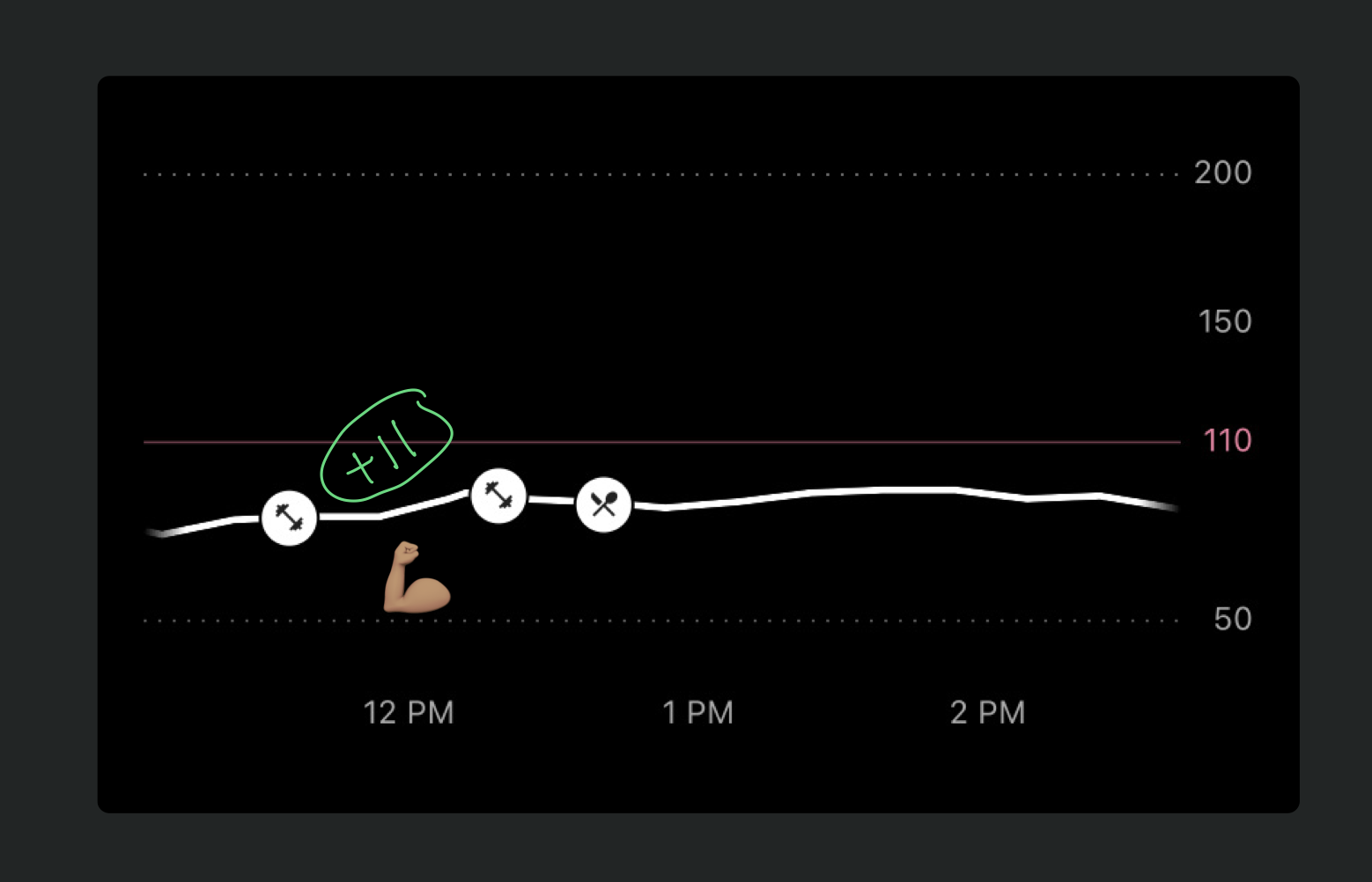

A: Stress has a fairly universal response throughout your body, whether it’s mental or physical. Stress tends to increase your blood sugar as your body mounts a response against the perceived threat by releasing glucose (energy) from storage. This might be why my blood sugar ticked up a bit while exercising in a fasted state.

Q: Does the speed of eating influence your glucose response?

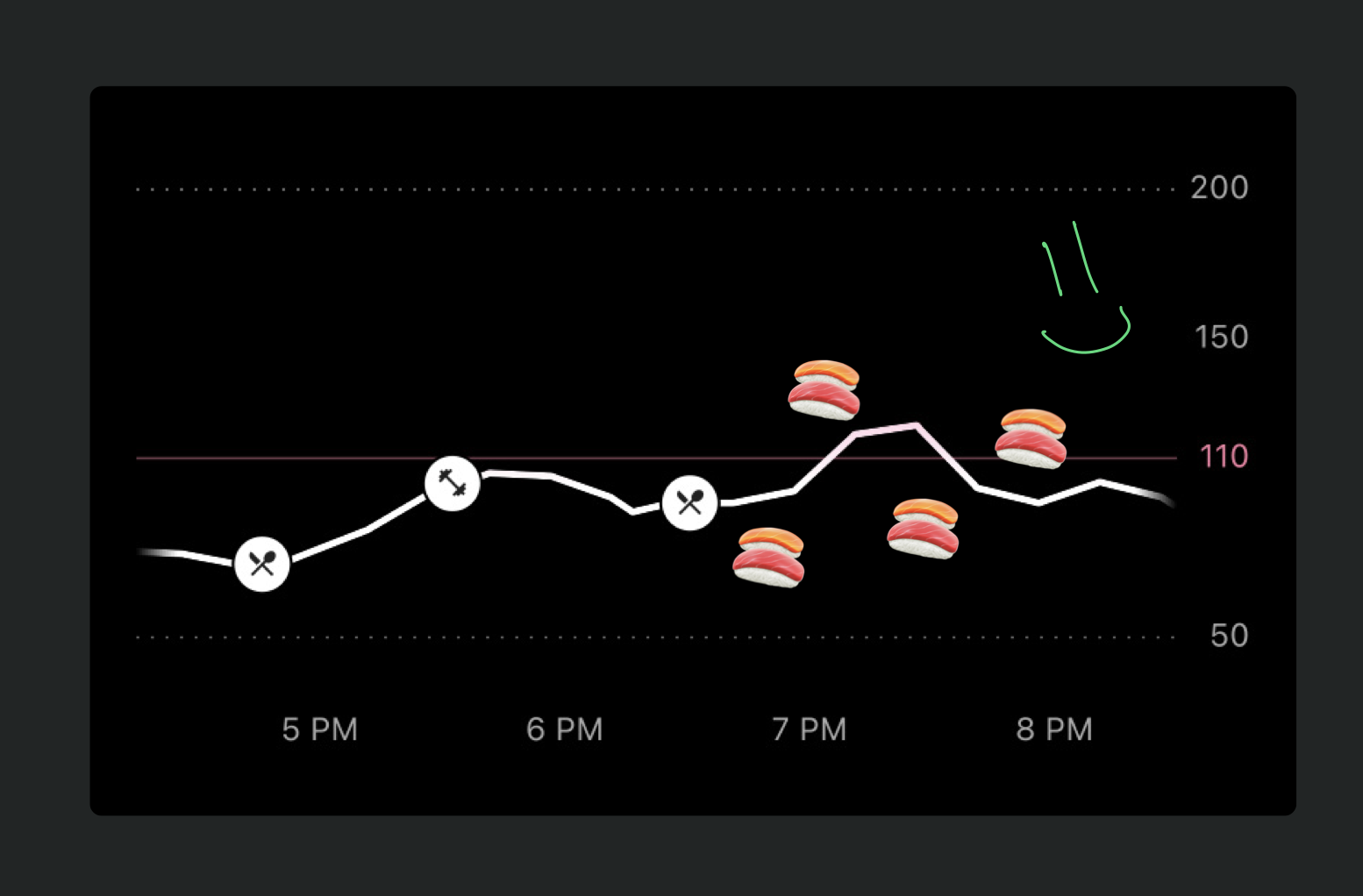

A: Definitely. After consuming something, your body needs some time to process it. If you eat super quickly, it will need to process more food at once, spiking your blood sugar more quickly than if you ate slowly. For myself, I noticed that my blood sugar barely spiked when eating a huge meal of sushi & hibachi (carb central) because it was distributed over a few hours.

Q: How does your blood sugar influence sleep?

A: It influences it in a handful of ways.

- If you're hypoglycemic (low blood sugar), you'll likely get woken up in the middle of the night.

- Your blood sugar naturally dips at night, but dropping below a certain threshold is a signal for your body to wake up and find some food.

- Eating too close to bedtime can cause this, since a spike in blood sugar following a late-night dessert will lead to a crash later and wake you up.

One problem I've also personally had is night sweats, which are commonly caused by eating too close to bedtime.

Q: How does alcohol consumption influence your blood sugar?

A: Intuitively, I thought that drinking alcohol would increase it sharply, as you're basically scarfing down liquid carbs. However, it turns out that alcohol actually decreases your blood sugar. Your body goes into hypoglycemia and recruits insulin to clean up the toxins found in alcohol. This is also why you get the "munchies" when drunk — your blood sugar tanks and your body thinks it needs more food.

Overall Reflections

From this month of using a CGM, I've come away with a handful of actionable insights for balancing my blood sugar response:

- Take a brisk 15-20m walk after a big meal

- Eat slowly and chew more

- Pay attention to how your body reacts to certain food (for me rice > pasta and bananas == nope)

- Strategically use glucose disposal agents (see below)

- Eat the protein and fat of a meal first as the order of how you eat calories is important for blunting your glucose response

Another important learning was that almost anything that you consume / do either increases or decreases blood sugar. Things in the latter group are known as “glucose disposal agents” and can be used strategically to blunt a blood sugar response. Andrew Huberman goes into great detail in this podcast, but here are some well-understood agents, some of which might seem surprising:

- Light movement (hence the 15-20m walk)

- HIIT (high-intensity interval training) in afternoon without food afterwards

- Cinnamon — yep

- Lemon / lime juice (possibly due to acidity)

- Apple cider vinegar

- Berberine

- Metformin

I've also learned that healthy eating patterns compound and last more than just the hours afterwards. There was a noticeable effect that an egregious meal had on my sleep, and thus my energy levels and discipline the following day. A few good meals in a row can lead to a mental state in which you continue to make good decisions, while a few bad meals can throw you off track until you will yourself back on track.

As for my next experiment with a CGM (oh there will definitely be a next one), there are a few things that I'd want to try out and change to collect even more data:

- Beyond 22 hours, I didn't measure the effect of a fast on my glucose response. I think it'd be fascinating to see how my levels fluctuate as I transition into ketosis.

- There are some supplements that I occasionally take like Athletic Greens for all-in-one nutrition and LMNT for electrolytes. I take these when I am technically "fasted" so I'd like to see if there's a noticeable blood sugar response.

- Recently, I've been taking activated charcoal when I've had an egregious meal or stomach ache and it works surprisingly well. I'd love to test if there's some kind of blood

magicsugar relationship.

Alright friends, that’s it for now. Have you ever considered experimenting with a CGM before? Is there anything that you know about blood sugar or metabolic health that I haven’t mentioned in this piece? I would love to know and connect on Twitter!

Footnotes

-

I recall him mentioning this in some podcast somewhere but I couldn't find the source. ↩